- Campaign workers can have vastly different salaries even for the same job title.

- How much they get paid depends who they work for.

- Working on a presidential campaign won't necessarily mean getting paid more.

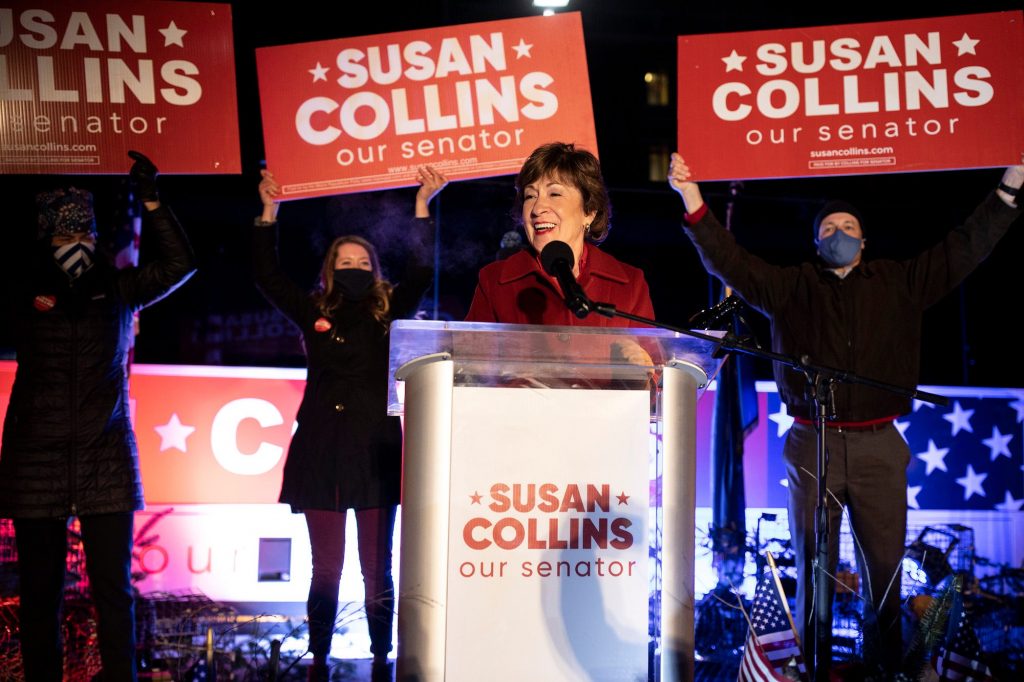

In 2020, Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine faced the first tough reelection race of her long congressional career. Democrats made unseating her a top goal after Collins, a moderate by her party's standards, voted to confirm conservative Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

So Collins tapped her longtime chief of staff, Steve Abbott, to temporarily leave his job on Capitol Hill and manage her campaign, as he'd done before.

Collins won re-election. But Abbott's work came at a premium, as he disclosed earning $426,666 for the entirety of his work on the 2020 campaign, according to an annual personal financial document he filed with the US Senate. The document indicates that his wife, Amy Abbott, received a salary from the Collins campaign, too.

Abbott is among a group of top-tier Capitol Hill staffers to reap the rewards of hitting the campaign trail. In fact, joining campaigns has become a common way for congressional staff to pad their taxpayer-funded incomes, according to an Insider review of congressional financial disclosures and Federal Election Commission filings.

Members of Congress frequently hire campaign talent directly from their official Capitol Hill and district office employee pool. Job opportunities on campaigns range from communications professionals to policy directors and senior advisors.

After all, congressional staffers know their boss's policy positions, their states, and have a deep sense about what's important to constituents. Plus, the arrangement can mutually benefit staff. A year or less spent on campaign-only work can pay more than a comparably long stint in a congressional job, particularly at the most senior levels, the documents show.

Some take weeks or months off from their Capitol Hill jobs to devote themselves fully to campaigns. Others hold down jobs on the Hill and work on campaigns after hours or throughout the day. Some scale back their official hours, while others just see their congressional work bleed into nights and weekends.

Either way, earning the extra cash requires taking on added responsibilities and navigating new ethical standards.

For many good government groups, the divided duty is concerning.

"The obvious outcome that could occur is that more staffers will look to the campaign for money and be more dedicated to the campaign than doing the work of Congress," said Kedric Payne, a former deputy chief counsel at the Office of Congressional Ethics who's now a top attorney at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan watchdog organization.

But many congressional staffers defend the practice. One former Democratic House staffer said colleagues viewed it as "an opportunity for them to prove themselves" and helped to underscore "that elections really matter."

"If you have had the experience of phone banking for a campaign and you're bothering voters during dinner, then you are a better phone answer when they are calling you with a problem [at the office]," said another former Democratic congressional staffer. "You have been on the other side of the table."

Bradford Fitch, president and CEO of the Congressional Management Foundation, told Insider that, in his experience, congressional offices would make arrangements if a staff leader was going to be on the campaign trail for a while or scaling back hours.

He said the organization, which works with members of Congress and management staff, counsels staff to clearly track when they're doing campaign work and to spell out, in writing, which responsibilities will be handed down to other staff while they're out.

"We have not seen a lot of managerial problems arise from these arrangements," he said.

Cashing in on experience

Insider took a closer look at certain campaign salaries by analyzing 2020 personal financial disclosures of senior congressional staffers, which are only available to the public via a handful of computer terminals at the US Capitol complex in Washington, DC.

Many of the salaries Insider uncovered are imprecise because staffers inconsistently reported the details of their pay in their disclosures.

Staffers who reported how much they earned on campaigns also didn't tend to disclose the amount of time they worked for the pay they received. The pay can often be given in bonuses in addition to biweekly amounts, one Republican senior staffer told Insider.

Nevertheless, the revolving door between congressional work and campaigns can be lucrative, the records show.

Abbott's financial documents are just one example of how piecing together the pay for campaign leaders is difficult.

For instance, payroll data from the FEC further breaks down Abbott's pay to show what he was making every two weeks. An Insider tally of the numbers found Abbott made $184,673 from the campaign in 2020 alone, including a $52,302 payment on Election Day. The total was an increase from the $109,385 Abbott reported making as Collins campaign manager during the 2014 election cycle.

Neither Abbott nor Collins' office responded to questions clarifying the terms of his salary. Most people named in this article did not respond to questions from Insider about the amount of work they did for the pay they received.

Another similar discrepancy was in the financial documents for Ali Black, who currently serves as communications director for House Republican Conference Chair Elise Stefanik of New York.

Black disclosed earning $131,932 during her time as the Trump 2020 campaign's deputy director of communications. FEC records show that Black did slightly better than that, pulling in $135,438 in straight payroll payments.

Vanessa Valdivia, who currently serves as communications director for Democratic Sen. Alex Padilla of California, disclosed earning $82,875 from handling press for Democratic Sen. Gary Peters' 2020 reelection effort in Michigan.

FEC records show that Valdivia earned significantly less, detailing $60,660 in salary payments from Peters' campaign. The same records show that she earned $9,354 from Democratic Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, bringing her combined haul from both campaigns in 2020 to $70,014.

No political pay standards

So, how much money can someone expect to make working a higher-level job on a political campaign?

The FEC, or any other governmental body, provides no guidance to campaigns on what they should pay their workers. The campaigns alone determine how much they compensate staff members.

But federal records show just how much campaign pay can vary.

Take Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who ran for president in 2020.

FEC data show she paid her campaign manager, Roger Lau, about $13,000 a month — for an annualized salary of $156,000. Lau, who is now the deputy executive director at the Democratic National Committee, previously worked on Warren's Senate campaigns, and was Warren's state director in her congressional office.

There, his salary was similar to what he was getting paid on campaigns, according to the nonpartisan Congress-focused research organization Legistorm.

Warren, who ran her presidential campaign on a policy-heavy platform using the slogan, "I have a plan for that" paid the head of her policy team, Jon Donenberg, the same salary she paid Lau and the rest of her senior staff.

Donenberg was Warren's legislative director before the election but is now her Senate office's chief of staff.

The congressional promotion came with a salary bump. In 2018, Donenberg made $153,857 and in 2021 he made $171,774, according to Legistorm.

Other staffers come to the Hill by way of campaigns. Misty Rebik, who was executive director of the 2020 presidential campaign committee Friends of Bernie Sanders, reported earning $110,909 for the time she worked on Sanders' campaign. She now serves as Sanders' Senate chief of staff, where she earned $115,292 in 2021, according to Legistorm.

Republican Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah paid his 2018 campaign manager, Matthew Waldrip, $150,000 for the time he spent working for the campaign, according to his financial disclosures. Waldrip went on to be Romney's chief of staff, where he made $172,790 in 2020, according to Legistorm. He now works for the investment firm Dauntless Capital Partners.

When Alabama GOP Sen. Tommy Tuberville joined Congress in January 2021, Jordan Doufexis disclosed that he made $47,500 working as new media manager for the former Auburn University football coach's successful 2020 campaign. The documents don't specify how many hours or months of campaign work Doufexis' pay represented.

Now Doufexis works on Capitol Hill for Tuberville. He earns a lot more, making $121,889 in 2021 for his work as a state coordinator, according to Legistorm.

In some instances, campaign pay, which is funded by private donors and special interests, can exceed Capitol Hill pay, which taxpayers fund.

Abbott's chief-of-staff salary for Collins reached as much as $169,459 in recent years. That's almost as much as the senator herself earns as a federal lawmaker, but less than he makes leading Collins' campaign.

The same was true for Ali Black, who was making $86,011, according to Legistorm, in her job as press secretary for Republican Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming. She boosted her salary by at least $46,000 from when she was working for the Trump campaign.

A 'salary cap'

Some congressional staffers work on campaigns part time while still holding onto their Capitol Hill or congressional district jobs.

The practice is fairly widespread, though it has its limits. Senior congressional staffers earning a minimum of $135,468 a year for their Capitol Hill jobs are allowed to earn no more than $29,895 working on campaigns, according to ethics rules in both the House and Senate.

Financial disclosure documents uncovered a few examples of senior staff taking this route.

In 2020, for instance, Vanessa Moody reported working simultaneously as the state director for Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas while also consulting for his Senate campaign.

Moody reported making $27,500 for the outside work in her financial disclosure, which FEC data show was the tally from January 2020 to soon after Election Day.

Aside from salary caps, the House and Senate ethics committees have rules about what staffers are and are not allowed to do if they want to take on two jobs. For instance, they cannot take campaign-related calls from congressional offices. So if they're at work when they get an elections-related call, then they have to step outside.

Sometimes staffers take time off for a few weeks or months while other times they work a double shift — first on Capitol Hill or in a district office, and then go home, to a coffee shop, or to a political party's headquarters to do campaign work.

One former staffer told Insider that during the 2020 election cycle he would sit at home and have both official and campaign computers open given that everyone was working remotely to avoid COVID-19.

Potential issues are subject to scrutiny by the secretive House or Senate Ethics Committees — though they rarely act — or by the independent, nonpartisan Office of Congressional Ethics on the House side, which keeps its investigations private until they conclude there's reason to believe a legal or ethical violation occurred and then refer matters to the Ethics Committee.

The office could work much better if it was permanently authorized and had subpoena power, said James Thurber, a professor at American University and congressional ethics expert.

"They've done a good job with the resources that they have," he said, "and the politics that are surrounding them, and also the limits that are placed on them."

Congressional chiefs of staff, press secretaries, and schedulers are the essential personnel that tend to inhabit both worlds, said one former congressional aide who requested anonymity because they routinely advise members and campaign staff about ethical issues.

Staffers who are allowed to work in Senate offices but also handle fundraising matters are called "political fund designees" and every office is allowed to have up to three of them.

Others who elect to flip-flop from one world to the other, the advisor said, participate at their own peril.

"Some people are very ambitious and really into politics," the advisor said. "And if they're not volunteering for their boss's campaign, they're probably going to volunteer for somebody else's."